Behind the Scenes in Blue Heelers

By Peter HaddowEditorial Note

Blue Heelers, Australia's top-rating TV drama series, has screened over 250 episodes. Martin Sacks, the actor who plays the character Detective P.J. Hasham, says the show's appeal is very simple: "It's good guys and bad guys with the case wrapped up in 43 minutes. Then we sit in the pub and slap each other on the back and say, 'Good one boss, case solved'." Martin also stated: "It's just seven people in a country town and there's a story each week and the viewers are interested in finding out how the characters deal with that show's particular story."

The APJ now gives police and readers generally a look behind the scenes at what is involved in producing a high-rating TV police drama series.

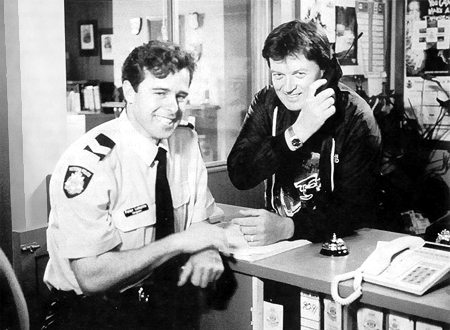

Sergeant Peter Lukaitis (Melbourne Police) on set with Peter Haddow (author).

"AND ACTION!"

Those were the first words said on set during my first location shoot at Blue Heelers. It was said by the First Assistant Director, David Clarke, and within a second of saying those words the actors moved in front of the camera and said their lines. It only took about 30 seconds and the Director, Mark Piper, then said, "Cut!"

This was my introduction to the world of television. Where actors learn scenes which average 30 to 60 seconds and the support crew spend an hour or more setting up the lighting, the props and casually joke with one another. Where the director and assistant director discuss and work out any changes in their proposed shooting plan. Where the police adviser is asked to clarify something in the script which had not been obvious in the preceding weeks or an actor seeks your advice. During the next 12 hours this is what it is all about and initially it is interesting and challenging.

I was told by the Producer, Ric Pellizzeri that being a police adviser would give me a unique view of the film-making process. There are few people who are involved in every step of bringing a story idea into reality and even fewer read every draft of every script. Those same few also have the opportunity to present their ideas and thoughts to the many scheduled and unscheduled script meetings.

Blue Heelers was originally going to be about city police with the working title 'Boys In Blue'. Michael Winter, who in 1990 resigned from the New South Wales police, contacted Southern Star Productions and during story meetings (where story lines are developed largely calling on the experience of serving and former police officers) he talked of his experience as a country copper at Young. Winter's stories (he had spent seven years as a police officer) convinced Hal McElroy that setting the series in the country was a better option and come April 1992 production on Blue Heelers had started. Why the name Blue Heelers? McElroy had given the show the working title of 'Leave It To The Country' before Michael Winter suggested Blue Heelers, the local nickname for the 'tyre biters', the Highway Patrol, at Young. The expression Blue Heelers was sold to the public as being a well-known police expression while in fact it was known only to a select number of police in Young.

Following the pilot episode Winter became the original police adviser for Blue Heelers. He left at the end of episode 54 to return to New South Wales to live and work on Water Rats. He has since moved on and continues to work in the medium as a script writer and occasionally as an actor.

My first day at Blue Heelers was in the Writers' Cottage located near the Channel 7 studios in South Melbourne. It was the day before Australia Day and the streets of Melbourne were deserted with nearly everyone taking advantage of a long weekend. But not those in the Writers' Cottage. I was greeted warmly by those in the Script Department and this first day was spent discussing story lines and the direction in which characters were headed such as 'Should PJ end up shagging Maggie?'

The next day, a public holiday, and everyone at the Writers' Cottage was back at work for another full working day. The Script Department (the Engine Room as I came to know it) started work a week before the actors, crew and most of the management. I was glad when they stopped work at 4.30pm as I had a birthday party to attend and did not want to be late. Little was I to know it was going to be a long time before I was to get another 'short' working day.

There were various drafts of scripts that had to be read and commented on. It was very time consuming and required a lot of research to ensure that things were right. Then there were meetings which required your concentration and input — Production, Directors, Story and so on — plus the many unscheduled meetings in the Script Department. All necessary to keep the wheels moving on the television treadmill. Even on weekends time was not your own. There were always five to ten scripts to take home and work on. If reading them was all that was required then it would have been easy work, but it wasn't that simple. You had to ensure that the police side of things was accurate (or accurate enough for the generally ignorant audience) and try to come up with things to improve the scripts.

At first it bothered me that the series was screening things I knew were technically incorrect or implausible but after a few months I did not think about it. Michael Winter had felt the same way when he started at Blue Heelers and warned me that initial feelings of frustration would be replaced by a 'que sera sera' attitude. It did concern me that my former work colleagues would pick up the inaccuracies (they usually let me know!) and the stretching of truth, but over time it did become 'que sera sera'. By then I had, for months, been repeatedly reminded by everyone, from producers down to script editors, that the series was "a drama, not a documentary".

Michael Winter and I helped compile more than 100 slang expressions for inclusion in the Blue Heelers Bible — a comprehensive 55 page book which was given to script writers. It contained the storylines and history of the main characters and the mythical town of Mt Thomas. Our section of police slang was important as it added a touch of credibility to the series, particularly for serving and former police.

After a few months in the job Ric Pellizzeri told me a former police officer offered to do my job for no pay. It would not be the first time retiring or retired police would approach the producers directly or indirectly about being a police adviser. I quickly learned fast that my job was about as safe as anyone's in the television industry. About the same time as this approach was made known to me one of the script editors was sacked and replaced, all within the space of a few hours.

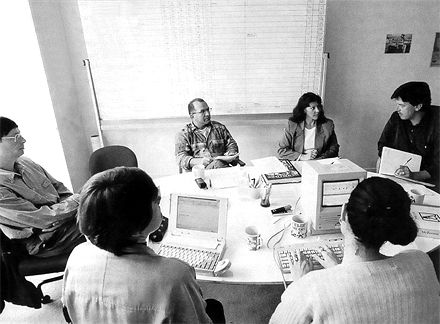

Script writer's meeting: Piers Hobson (writer observer), Ric Pellizzeri (producer), Isabelle Dean (writer), Peter Haddow (police adviser), Emma Honey (script editor at keyboard) and Caroline Stanton (story editor).

Whenever someone said to me, particularly during my first year, that Blue Heelers was "no Phoenix or Janus" I would acknowledge the comment but add, "That's right — Blue Heelers is number one in the country."

This was no put down but the truth and besides, ratings do not necessarily indicate quality but they do indicate the number of people who view a program. I personally enjoyed and religiously watched Phoenix and Janus but it was not seen as good drama, more "a documentary" by those in the commercial world. It would not have survived on any channel other than the ABC. Its rating figures (i.e. its financial viability) were less than half that achieved by Blue Heelers but it was seen by many to be 'The Police Gospel According to TV.'

At Williamstown, during the third week of filming, children swarmed around the actors seeking their autograph. One small girl asked for mine. I told her I was not an actor and she said she didn't care but she loved Blue Heelers. Children in fact were probably the show's biggest supporters at first. Before long the girl had not only my autograph but just about everyone in the crew. Whether she got to the actors I do not know but she would definitely have the only autograph book in the world containing all the signatures of the Blue Heelers crew.

Everyone loves success and being connected to it and those at Blue Heelers did not at first feel this connection at all. It took quite some time before there was general public, police and critical acceptance of the series. At first you would almost whisper who you worked for. You felt you were being looked down on, as if you had walked on someone's white carpet and wiped dog droppings from your shoes. It was something felt by almost everyone connected with the series. I remember Lisa McCune saying she did not start to feel recognised and part of something good until 1996. There was a change in public and police perception and more importantly, critical acceptance. Soon everyone attached to the series was seen in a better light.

In the middle of March 1995 I had my position confirmed, the producers saying my input had strengthened the episodes. Then at a story meeting, on the very same day, a story line seemed too fantastic to me and I, naturally, expressed that point of view. Caroline Stanton, the story editor, then jumped on me saying I had to choose whether to work with them or not at all. Michaeley O'Brien, a script editor, came to my defence saying that I had given positive criticism and after a few glares around the table, we went back to work on the script. Tightening and adjusting, all in the name of making the script appear acceptable to the general public. Not always agreeing with one another but always working towards that fine medium where there was a balance between fact and fiction and feeding that all important monster, Drama. As police adviser it was my job to bring a police perspective to the series, and from a personal point of view, reality.

At a crime scene being shot in Werribee I saw that Damien Walshe-Howling and Lisa McCune were walking on the wrong side of the tape. The Director, Karl Steinburg, agreed that realistically it was not right but for television purposes ("Drama") it looked better, so it remained on screen.

"It looks good," he said.

Another time the Blue Heelers police car was seen in an emergency situation. The blue and red lights were flashing but there was no siren. I brought this to the attention of the director and he told me not to worry about it. When pushed on the matter he advised that the siren was always dubbed in during the editing process. As was music and anything else that would interfere with normal speech being recorded during filming.

During the filming of another episode support actors approached and told me of problems they had playing homicide detectives. They asked for advice on how they should stand, move and handle things. They were having trouble with the script and believed (rightly) that the detectives were not authentically written. I told them of homicide detectives who had impressed me and how they did things.

To their credit the actors tried to include what had been suggested to them, within the limitations of the script. They at least displayed more confidence and watching the edit a week later it was obvious they had done their best when compared with what I had seen during rehearsals. On another occasion, for an episode deemed to be especially important, I was asked to get the actors to work with the Homicide Squad for a few days but it was received without enthusiasm from the Squad (unless Lisa McCune was involved!) and subsequently they had to make do with my input.

Two months after the script editors had mocked Michael Winter for putting on weight during his time with the series ("It's the biscuits that will get you," he said) I noticed that my clothes were shrinking, and fast. The truth was that at the end of 1996 I had put on more than ten kilos. Not only was the availability of biscuits at meetings responsible but so was the constant sitting in the office, sitting in the car and then sitting at home reading scripts. I worked it out that 95% of my day involved being physically inactive while the brain was in overdrive. It was difficult to do anything about it because of the workload and the sense of being on a fast moving treadmill.

At one party my wife and I went to, I read a script in the host's bedroom — the script had to be with a script editor the next morning. My wife thought I was being rude but it was either that or I would not have gone anywhere. I didn't want to start reading the script at 2.00am or let the Editor down.

With so many scripts to read I found that I was taking them with me everywhere. I'd take a train to the football just to read a script and during the breaks in the game. If it was a one-sided game (except against Collingwood or West Coast Eagles) I'd spend the game just reading and writing on the script. It seemed that every moment of your day was spent either discussing, reading or dreaming of bloody scripts. To a lot of people it was glamorous but there was more to just reading a script.

You had to look for faults in dialogue, police attitude and make suggestions in the hope to improve on the draft. Martin Sacks had asked me one Friday about wearing a suit and I told him most detectives wore one. He wanted to accurately portray a detective as best as possible and as the producers wanted him to wear casual clothes I tried to convince him it was better to show the correct attitude for a detective than merely wear a suit and not be convincing. I reminded him Kojak had a lolly pop, Columbo a trench coat, Sherlock Holmes a funny hat and pipe so maybe PJ's idiosyncrasy was casual dress. Obviously during the weekend this bothered him. The next day I got a terse phone call from the wardrobe lady.

"Don't tell actors anything," she said.

It was something I had been told often — by almost everyone who was not an actor — from Day One. I began to wonder what you could say to anyone, particularly actors, without fudging the truth. Generally actors are insecure by nature and like to be liked and accepted. For me it was the proper thing to tell the actors the truth, but knowing that this could upset someone else down the line was a concern. It was easier not to spend a lot of time with the actors as it meant less repercussions if they asked you questions and you were a little too candid. Even simple questions relating to forensic science could present a problem as the actor would often challenge the Director about the fast tracking of scene examination (what would in reality take a month or more to get a result would be seen as 2 minutes) and naturally delay things a bit.

I was on my way to a Rolling Stones' concert when my mobile phone rang. I felt inclined not to answer but duty called. It was Peter Askew, the Line Producer, asking me questions about firearms. The concert was about to start and I dreaded the thought he would ask me to come back to the studio. I was glad when he was happy with what I said allowing me to be able to enjoy the concert. Feeling safe, I switched off the phone.

Clarkefield was the location for filming of one episode. I thought the main guest actor looked familiar as he practised karate kicks while deep in thought. During a break I told him he looked like Colin Hay, the writer and lead singer for Men At Work. He grinned and told me in a Scottish accent that he was indeed Colin Hay. Then he dropped the Scottish accent and talked to me in an Australian accent. He then sparred with Damien Walshe-Howling for a few minutes before the director, Richard Sarell, called everyone together for the scene.

Afterwards I would speak to Hay and arrange for him to sign my copies of Men At Work albums. Little did I know the strife this would cause. Colin signed my CD and LP covers with humility and was particularly thrilled that I had copies of his solo albums. For this sin I was given some chiacking. Story Editor Caroline Stanton told me that what I did was known as "Star F**king" and having 'stars' sign autographs for crew was frowned upon in the industry. I asked whether she would have Paul McCartney, a favourite of hers, autograph the Beatles albums she cherished if he came on Set? Producer Ric Pellizzeri told me my actions were "embarrassing".

I still don't see what the fuss was about as apart from having him sign the albums he was not treated any differently to anyone else. In Australia actors are generally referred to as "F**kin' actors" or if they cause a problem it is excused by the comment, "What do you expect, he/she's an actor."

Actors are generally not put on a pedestal like they are in the USA and elsewhere in the world. Although if you get on the wrong side of a lead actor then "you eat shit if you want to keep your job" as John Greene, the location manager warned me. They eat with everyone else and are treated as if they are just one of many parts to the show. At the same time though they promote the series and are paid very handsomely for the demands on their time.

Apart from the advice given to me by the location manager there were other rules to stick by. On set if your mobile phone rang during a take then you had to shout the crew a slab of beer. I got caught out once to the loud refrain of "slab!" and dutifully paid up at the end of the week.

To keep myself up to date I maintained contact with former work colleagues and friends in the police force. I would take several police to lunch or dinner and absorb stories and get 'refresher courses' on anything from finger-printing, arrest procedure, use of the baton etc. It was important to keep up to date and also to reinforce new procedures into the mind of serving police. I knew things were looking good when Ian Geddes, an Altona North detective, visited a location shoot in Williamstown. He told me that he had been in the next street investigating a burglary but had trouble convincing the resident he was not an actor!

Peter Haddow (police adviser/actor) and Mark Piper (director) with actor John Wood (background). On location in Williamstown for episode 80, 'Tough Love'.

On some location shoots visiting police would talk to an actor or director; sometimes giving advice. On one occasion a great piece of acting by Damien Walshe-Howling had to be cut from the final edit when he said to a villain he was arresting, "You have the right to remain silent..."

Initially everyone in the producer's office was thrilled with this particular arrest scene. I considered the 'Drama vs Documentary' dilemma in my mind and kept quiet for a second, but it was too much for this patriotic Australian to bear.

"That can't go in like that," I said.

They tried to dub in the caution as used by Victorian police but it did not match with Damien's lips and so the scene was cut altogether. Damien told of a visiting police officer who told him "it's all right" to use the American caution when obviously it was not. Subsequently I tried to be on location more than usual but you could not be everywhere.

At the start of holidays I intended to spend the first few days reading the 15 or more scripts and then enjoy the unpaid break. However, the lure of going into relax mode was too great and two days before the end of the holiday break I would be locked in my office for hours and subsequently start the return to work tired. It was on these occasions when I remembered the philosophy of Elizabeth Symes, another producer who said, "Do the hard stuff first, then relax."

The days were always long and towards the end of my contract, bordering on tedious. I would spend on average three days a week in the Writers' Cottage putting in ten hour days. On the two days of location filming you could spend up to 12 hours and that did not include the travelling to get to places such as the You Yangs, Williamstown, Clarkefield and Werribee. Sometimes with an afternoon shoot, you were at work for 16 hours and still had to read a script before arriving at the Cottage the next day.

I tried to work smarter by wandering away from location shoots and finding a quiet spot but it was often impossible. People would want to talk to you, seek your advice or you would just want a break from reading the bloody scripts. At home I would sit on the couch with my wife and together we would watch television; me with a script in one hand and pen in the other. It was not unusual to wake up still on the couch but covered with a blanket, with the script still unread.

For some episodes I was asked to write the D24 dialogue which I did at home as there was no opportunity to do it at the Writers' Cottage without constant interruption. It took more than six hours to write the ten pages of script. The next week I was in the studio recording the voices, five in fact. It amused me that the producers paid an actor hundreds of dollars for ten voices and got me to supply five for no cost other than my usual pay. I would have been happy to have supplied another ten for half of what they paid the actor. However it was great experience and a bit of a buzz when someone would ask who supplied the voices. There were other occasions when I would appear in an episode either as a police officer or someone in the crowd. Great experience.

Director's meetings took place on Wednesday afternoons and were generally very long and mentally taxing. It was the last chance for the script to be revised and the story editor, Caroline Stanton, was not anxious for many changes as it meant significant work for the script editor and herself.

From my view point the story editor and script editors had the biggest work load of the Blue Heelers production team, usually with little recognition from the cast, crew and general public.

On one occasion Script Editor Peter Dick was so involved in his work he answered the Blue Heelers script office phone with, "Good morning Mt Thomas Police Station."

Unfortunately, and many times fortunately, many of the directors had objections to certain actions or story lines or language. It resulted in lengthy discussions and compromises and usually meant long hours in front of the computer for Stanton and that episode's script editor. They were generally paid in one week what the average police officer earns in a month but they certainly earned it. It was not an easy quid and in reality, the success of the series rested largely with the quality of the scripts. You could have Robert De Niro or Meryl Streep in their prime starring in a film but it would be no good if the script was not right.

On one occasion Script Editor Michaeley O'Brien faxed copies of my notes of a script to the script writer. The notes were quite lengthy and O'Brien thought rather than re-type them she would send them as they were. She was pleased at saving herself a lot of time as like us all, she was under a lot of pressure. It was only when she faxed them and then told me what she had done that her grin disappeared. I asked whether she had read all of my comments as at one point, in the early hours of the morning, I had been less than flattering about the writing.

Writers like any artists are generally sensitive creatures and it pays to have a thick skin. Fortunately the writer was outwardly unconcerned and continued to provide scripts to Blue Heelers and I did not receive from her any voodoo doll. O'Brien would from then on check with me first to gauge my impressions of a script before sending my notes to a writer.

It seemed as if the only people who got any recognition were the actors, directors and producers. While the story editor, script editors and script writers were generally thought of inconsequential they appeared at the top of the credits. The police adviser was considered even more inconsequential and usually appeared at the bottom end of the credits, behind the location manager, accountant and cleaner.

Apart from Lisa McCune and Martin Sacks, the actors were in reality on set for considerably less time than anyone else. Taxis generally ferried them to and from the set whereas others in the crew had to use their own transport. They usually had one sentence to remember for each scene which lasted less than a minute. If you spoke to them about a scene they did an hour earlier they generally could not remember it. Most actors had a short term memory and retained only what was necessary for the forthcoming scene, much like police who remember the case they are about to give evidence in but not, verbatim, the evidence from their previous case.

There was a pecking order amongst the actors with John Wood being number one. Actors who were paid to talk (there were two types — the paid to talk actors and the actors who did not talk) liked to have something to say in each scene they appeared in even if it was not necessary. It was not unusual to hear an actor complain about sitting in a chair minding a prisoner when they felt they should say something in the scene. In interview room scenes generally every actor had to have some dialogue, whereas in reality perhaps the informant would do all the talking. I once showed an interview video and everyone was surprised at how the police did not yell and scream like they did in the series. It seemed a shock that the real police were polite and well mannered, almost like the best friend of the offender, and one officer did all the talking.

"It's not a drama," I said.

There was drama however when on location one day in Werribee an animal trainer had been hired to provide a crow to sit in a tree for a particular scene. The crow had one wing and it was obviously sick. It could not stand still and rotated around a branch while hanging onto it with its claws. The director was frustrated and spent hours trying to get it to do what its trainer had been hired for. Eventually a few minutes were shot but never used.

The following day however the director found a (wild) crow sitting in a tree and got the shot he had earlier been denied for no additional cost. On other occasions — and purely by coincidence — a koala would be in a tree, or a wombat or echidna would stroll behind the actors and there would be discussion as to whether it would look 'too cute' for the scene. Everyone was conscious of not going over the top.

Sometimes I would get phone calls from police, including those from interstate to complain about certain aspects of police procedure not being right. Most times I could only agree with the caller and explain that the producers were after "drama" and "not a documentary". Some police officers were quite aggressive in their criticism but it didn't worry me as I had done my bit and could only tell the producers and Script Department how it really was. Sometimes on location a director would check with me whether a police term in the script was correct. They had heard another expression used and when probed it was obvious they had heard it on an American TV series and it was part of their subconscious.

Use of accurate police language was for me important. Often the first draft of a script would come to me with American or British expressions which I felt were not appropriate for Australian, and certainly not Victorian, police. On one occasion I objected to 'toe rag' but the story and script editor refused to budge. Happily the actor who was to say it also felt, without any guidance from me, that the 'toe rag' expression was inappropriate and said something more Australian — which was comforting.

Some of the crew at 'Blue Heelers'.

On other occasions I would get phone calls from police complimenting me on the authentic use of dialogue. One time in particular was when I had coached Bill McInnes into saying 'TJF' for one episode. Apart from being bored easily he was always keen to give his character some edge and I was always happy to help.

In another episode McInnes was to check a house for a suspect but he was unhappy with what his character Nick Schultz was written to say in the script. Rather than say "No one's home" he said it in police jargon.

"It's a NCH."

I got quite a few positive calls over that one and it was even mentioned on Melbourne radio station 3AW one morning when Sunday Age Crime Reporter John Sylvester (ghost writer of the Chopper Read books), in the guise of Sly of the Underworld, talked about how authentic the language used in Blue Heelers had become.

"No Constable Home?" asked presenter Ross Stevenson.

"Close," replied Sly.

On the whiteboard in PJ's office I was required to write what would be seen on a typical CIB whiteboard and naturally TJF (The Job's F**ked) would appear from time to time to the approval of most police officers who spoke to me. If it was something I knew happened in a police station then I was happy for it to be a part of the series. If police felt it was authentic then I was getting somewhere. Occasionally props crew would check a police station and it was great to know the set was up to date.

On one occasion there was a script which I strongly objected to but was over ruled by the Script Department. They felt the police would view them being recalled to work in a drunken state as comedic. It was a view I did not share and felt unrealistic. When viewed by police public relations before the episode went to air the reaction was as anticipated. Blue Heelers went to great trouble and expense in re shooting some scenes and dubbing in dialogue to counter objections. When it went to air only those in the know could generally tell where the problems had been.

In one episode Tom (played by John Wood) the Senior Sergeant, was to be shot in the shoulder. The next episode called for him to be back at work with no apparent physical or psychological side effects. Knowing several police officers who had been shot, this script development and plot did not sit well with me. I argued that Tom should display some psychological and or physical problems. The story editor felt that this did not give any drama to the series adding that "our Tom is not like that." I continued to argue and eventually logic and compromise won with Tom wearing a sling in the succeeding episodes.

Towards the end of the first year one became less concerned about getting things too right. You knew that everyone was more interested in the dramatic qualities rather than the authentic qualities, even though some things continued to irritate. The Medical Adviser Lynley Hall and I joked that we would write our own script one day; 'The Revenge of the Police and Medical Advisers' which would end with the story, script editors and producers being forced to watch The Bill and Phoenix ad nauseam.

As a long time supporter of Australian Rules football, I encouraged the writing department to write about the game directly or indirectly. Particularly as the series was seen in 52 countries around the world. However, because football has 36 players you had to pay for 36 actors or a significant number to make the scene look real. As a compromise, to keep me quiet, football was mentioned occasionally but always in dialogue. More often than not basketball was the visible sport as it meant less actors had to be paid (money was always a consideration, just like it is in the modern police force) but it was a sore point as I felt we were further Americanising our great country. There was one concession though. I managed to convert two script editors into following the Kangaroos after taking them to a game at the MCG.

Keeping up to date was important. On one shoot the stunt coordinator rehearsed with the actors the actions he wanted them to do which looked good but were no longer the tactics employed by Victorian police. The stunt coordinator and I discussed this and I informed him about Operation Beacon and how it meant a different way of doing things. A compromise was met with neither the stunt coordinator nor me being totally happy. On another occasion I explained to the director how the police should make an arrest incorporating the new Beacon strategy. The director decided to shoot the scene in the old style as it was "more dramatic". At least I tried.

Later in the year I got permission from the police force to complete the five day Beacon Course while Blue Heelers took a short break. I found the course to be very enjoyable and it was great to work a 40 hour week again!

Probably the thing I liked the most about working on Blue Heelers was the interaction with the script writers. I would often receive calls from them out of hours for advice and try to help them through a passage which was causing them headaches. Even when I left Blue Heelers I would get phone calls from various script writers for advice, even on scripts not connected with Blue Heelers. Most were keen to get it right, even if it meant a lot of script restructuring. However, if it did not suit the script then what ever was inaccurate would remain. Changes generally only occurred if it enhanced the 'Drama'.

There were times when the actors wanted to go out on patrol with real police and generally this was organised without too many problems. When Tasma Walton joined the cast she visited a number of police stations and the academy to gain an insight into the police culture and her character. Of course there were many police officers only too willing to offer Lisa McCune a ride along on patrol but she had already been there.

Lisa and Martin Sacks had the biggest work load amongst the actors, being required on set most days and doing charity work on evenings and on weekends. Then during filming McCune would be mobbed by children seeking her autograph or wanting a chat, which she and all the cast members were always happy to give. The cast always looked after their fans.

In Blue Heelers the police are the heroes and everyone else the baddies, so it has to be from the police perspective. Everything was written from the police angle, much like The Bill, so when PJ shot someone it required some extra work. We were keen to get it right and some police officers came to the Writers' Cottage and talked about their experiences. Detective Senior Sergeant John Peterson checked the script with me so that whatever PJ did was within the Beacon Manual. I visited the Coroner's Office and read thousands of pages of a police shooting transcript.

In May 1996 I was contacted by Lawrence Money of Melbourne's Sunday Age newspaper. He was preparing an article on how I was supposed to be using contacts to get out of a speeding fine. Even though this was false he still ran with a watered down version. Blue Heelers, like the police force, has a strict code of ethics and I was later told by the Producer, Ric Pellizzeri, that had there been any truth in the story then I would not be working on the show anymore.

There were other signs which indicated Blue Heelers was no different to the police forces of the world. They were not only concerned about bad publicity but also just as budget conscious as any Chief Commissioner. The number of stunts, extras and guest actors were reduced to keep the show within budget. For example there could only be one stunt every three episodes (instead of every two). Stunts required driver doubles, fight coordinators, safety officers and it all costs money. Sometimes scripts had to be altered to take into account the budget cuts and some action scenes became dialogue scenes. Producers were always checking that filming was on time so that overtime payments could be avoided.

During rehearsals of a Wednesday morning William McInnes would generally read the script in a flat monotone and pull faces at some lines. Often he could be quite humorous. Martin Sacks would sometimes forget what page he was on. The actors generally highlighted their own dialogue and didn't read the whole script, which occasionally produced a problem with their understanding of the episode. John Wood often explained the importance of certain scenes as he always read not only his part but every page and knew the script.

During one episode in which William McInnes had a lot of dialogue he was able to repeat his part, word perfect, without any difficulty. The following week he was required to have little involvement other than to say, "Give me that," and "Someone radio for help!"

Whichever way he said these lines they never came out the way intended and for him it was very frustrating. When he said, "Someone help for radio!" his frustration boiled over.

"F**k me dead!"

Eventually he got it right. Even Lisa McCune, who generally had a faultless memory, could not get her lines right on one occasion. She had about 17 takes before she finally got it right and ironically the scene was very simple. She had to shut a car door behind an offender and tell her to put on the seat belt or something like that.

All the actors had their idiosyncrasies. Tasma Walton was forever talking on a mobile phone whenever she was not required for a particular scene; Lisa McCune was often singing (she has a very good voice) and was always surrounded by fans; Martin Sacks was not well coordinated and if there was something on the ground and he was meant to walk over it, you could generally be sure he would stumble over it.

The script department would occasionally be frustrated with the actors ad libbing rather than following what had taken them weeks to script. However it was generally conceded that the actors were the last check on the script and it was probably a good thing that they had a little licence. John Wood and Bill McInnes were the best ad libbers of the cast and generally added rather than detracted from the script.

Lisa McCune, Chief Inspector Wayne Carson, Chief Commissioner Neil Comrie, John Wood, William McInnes, Peter Haddow, Damien Walshe-Howling and Martin Sacks on the set.

Handcuffs were a problem for the actors. They could not release them in the time they felt was good for television and so Tim Disney (Lisa McCune's fiance) ground a pair down so that they could be released significantly quicker.

Why Blue Heelers has been such a success no one really knows. It is made cheaply (compared to similar series) and the cast were generally unknown when it started. Someone told me each scene was written for "people who knit"; for people occupied in doing something else at the same time such as the ironing, homework, or knitting. You did not have to concentrate in order to know what was happening. Sometimes the actors complained about the scripts but "anyone can come up with a line, but the script writers write the script."

There was only one time when the cast and crew appeared to be depressed and that was after 'Blue Murder' was shown on television. One cast member openly queried why he was involved in "crap like Blue Heelers." 'Blue Murder' was talked about in glowing terms for days and deservedly so. It was viewed as being easily the most outstanding Australian television production ever seen. The writing, acting and production were just world class but it only went for four hours whereas the Blue Heelers treadmill churned out at least 42 hours a year — something unheard of in any other country.

Originally the cast were not greeted as stars and nor were those behind the scenes. Even as a police adviser to the series my connection with the show was often met with a sneer. Lisa McCune said she felt that up until August 1996 she would generally be received in a lukewarm manner at private functions because she dared to work with such a low-brow show such as Blue Heelers. However, as the show went on its following and critical acceptance improved and subsequently everyone connected with the show began to feel an extra spring in their step. More police were watching the show which in itself was a significant endorsement. It was not unusual to learn of van crews coming off the road to have their meal break during the hour the series was being aired. At the end of 1995 Blue Heelers was the number one drama in Australia and has continued to be among the higher rating shows up until the time of writing.

In the two years I worked at Blue Heelers I found it to be a very rewarding experience. Everyone connected with Blue Heelers worked extremely long and hard hours with the pace never varying from one week to the next. If one person did not pull the oar with the same intensity as the others in the crew then it was quickly noticed. Despite the hours and level of intensity there was little staff turnover and few sickies.

Working behind the scenes changed the way I watched anything on the screen. You could tell where cameras had been set up and often knew how the story was going to end just by being aware of the formulaic style of presentation. Usually the villain was seen before the first commercial break so if there was a 'who done it?' scenario you knew where to look. And there was nearly always a twist towards the end of most episodes followed by a resolution.

Finally after two years and 100 episodes I ceased being the Blue Heelers police adviser. The Victoria Police took over the role in much the same way that it happens in New South Wales and some American states. In England producers continue to use former police to advise on series such as The Bill.

My last day at Blue Heelers ended the way it started. The director looking through the camera as the actors said their lines. Thirty seconds later he said, "Cut!"

About the Author

Peter Haddow is a former Victorian police officer and has previously written for the APJ (March 1999 issue "Jockey's Last Fall"). He is the author of 'Hoddle Street: the ambush and the tragedy' (Strategic Australia) and is presently writing a novel.